I’ve seen quite a few memes and posts recently, and I’ve had some conversations with friends and clients around this, about how it’s OK to not be OK. This really got me thinking; what does it mean when you’re not OK, and what can you do when you’re not OK? In order to answer this I need to get a bit technical and delve into Transactional Analysis, a framework around how we interact with others but also ourselves internally. This will help to understand what’s actually happening when we’re “not OK”, how to contain it, and how not to let it become its own feedback loop.

So is it OK to not be OK? Well, maybe, but first we need to understand how being OK works.

The O.K. Corral

The term “OK” is actually quite interesting, one source has it as:

“probably an abbreviation of orl korrect, humorous form of all correct, popularized as a slogan during President Van Buren’s re-election campaign of 1840 in the US; his nickname Old Kinderhook (derived from his birthplace) provided the initials.”

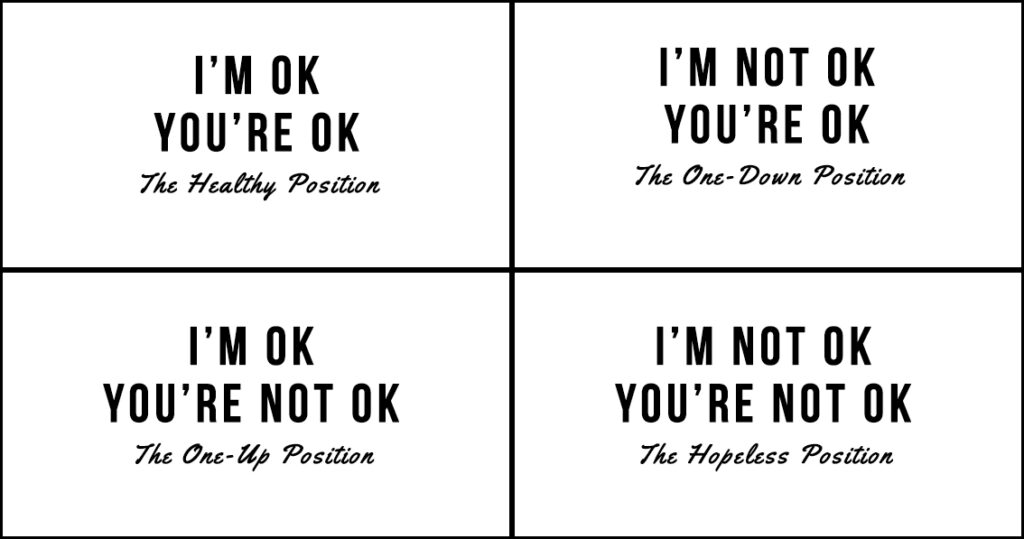

In Transactional Analysis we talk about Life Positions; it’s the position we take relative to ourselves and others in the terms of “being OK”. In this, “being OK” doesn’t mean “I’m fine, things are a bit so-so, but on the whole I’m doing OK.” “Being OK” means “I have choice, agency, capability, and ultimately control over myself and my thoughts.” This doesn’t, however, mean that someone who isn’t feeling OK is just fine and should pull themselves p by their bootstraps and get on with it. Let’s start with looking at the so-called (by some, and I like it, hence why I use it) O.K. Corral:

The two positions we have which relate to ourselves are I’m OK, as defined above, and I’m Not OK. When you’re “Not OK” in this sense what it ultimately means is that we feel like we have no control over our emotions, or our circumstances, or our mental state. Ultimately we have no agency. Things can feel overwhelming, daunting, hopeless, and depressing. Our emotions centre around sadness, despair, loneliness, and feeling abandoned. And this can happen even while being around other people. We have lost control of our lives and our thoughts.

The two other positions which relate to our external view of the world, or someone in particular, are You’re OK and You’re Not OK. This is our relative position to others, and if we’re in a Not OK state, how we relate to them can exacerbate and prolong the Not OK state.

I’m OK – You’re OK

This is the basic state of saying “I have choice, agency, control, and so do you.” It doesn’t mean “I’m sorry your hamster died, get over it.” It means that ultimately, regardless of the current situation, we believe that the other person is capable of making their own decisions and choices. We can still help each other out at times, support each other, and comfort each other, but we see in others the same potential as in ourselves. It’s when you get into I’m OK – You’re Not OK that there’s an issue.

I’m OK – You’re Not OK

In this position we say that we ourselves are OK, we’re able to make decisions, have agency, etc., but we’re saying the other person isn’t. We’ve taken away their agency and their choice and made them a victim of circumstance. Sympathy is a double edged sword, what we might mean as caring and compassionate can come across as condescending and patronising. Empathy, however, is an expression of I’m OK – You’re OK.

I’m Not OK!

Right now, you might be thinking: “But what about me, I’m really not OK! How do I get out of it?” That whole thing just needed explaining before we move on to the two I’m Not OK positions. The way they get explained will be best in the framework of how to get out of them. If you’re feeling definitely not OK, this is what you could do:

Step 1: Acknowledgement

The first thing, and the crucial thing, is really to acknowledge that “right now I’m really not OK.” That is key, and that can be incredibly hard because we don’t want to admit to ourselves that we’re not OK. “I’m fine, I get along, other people are worse off than I am.” The whole thing about how “men aren’t supposed to show weakness” or “I have to keep it together for everyone else.” Those thoughts which trivialise and downplay our own state actually end up making things worse because we don’t actually address the underlying problem. Eventually they’ll get too much, like trying to put a cork in a volcano.

Looking inwards and being honest with yourself and admitting that right now, I’m really not OK, allows us to be kind to ourselves, to not judge ourselves, and not feel like we have to put on a brave face. Some people do put that brave face on though, usually because they feel that they don’t want to let anyone down, or they feel pressure to behave in a certain way, or they feel they’ll be judged. Once we’ve opened ourselves to the possibility of being vulnerable and being honest with ourselves, we can start to move to a better place.

Step 2: don’t look beyond yourself

It’s incredibly easy when in an I’m Not OK state to look at others and think “That person is so OK, I wish I was like them, they have everything.” That’s the I’m Not OK – You’re OK position. Just like in saying You’re Not OK we’re making a victim, but of ourselves. It reinforces feelings of victimhood, of being in a “lesser” position. Everyone else will have their lives together, or the dream job, the perfect life, and know exactly what to do, whereas we are struggling and everything is beyond our reach and our control. The risk here is that we seek out others to drag them into our drama triangle but as a rescuer.

If we say I’m Not OK – You’re Not OK we’re really dragging everyone down with us. To take that position is to make victims of everyone. No one has any control, we’re all adrift in the sea of life, doomed to suffer, and should just give up now. This is an extremely dangerous position to be in because we can end up creating an echo chamber where we just get back the same thoughts.

To make one thing perfectely clear though: we can still ask for help. Asking for help isn’t taking that “One-down” position that I’m Not OK – You’re OK creates. Asking for help might actually be a good idea.

The reason why we shouldn’t be looking beyond ourselves in terms of being OK is that it doesn’t drag anyone else into our own drama triangle, and is the first step towards changing the only person who can actually do something about it. Who is that? Well, their nose is probably right in front of you right now. You.

Step 3: Self-care

A lot has been said about self-care and particularly self-love recently, especially during and after the pandemic. It isn’t something narcissistic if it comes from a place of genuine care. The greatest kindness we can give ourselves is to ask “What is it I need right now?”

It might not be immediately obvious. It might be something simple. It definitely shouldn’t be something which could exacerbate the situation, such as a drink (or several). Once we pinpoint the whole crux of the issue, we can then begin to address it. Is it something which I can do something about now, or can it wait? Is it within my control? If it isn’t, how can I get control over it? If I can’t control the whole issue, can I control at least part of it? At the very least we can control our response to it. Remember the whole idea isn’t necessarily to solve everything in one go, but to at least get out of the I’m Not OK state and into a healthier place.

The key thing here is kindness to ourselves. Don’t judge ourselves, don’t take what’s essentially a parental role against yourself, but treat yourself the way you would like someone else to treat you. Allow yourself to forgive yourself for feeling down, and say “Hey, it’s OK, we’re OK.”

Step 4: Do something

When we’re in our Not OK position, almost everything is too much effort, or not interesting enough, or we can’t be bothered. That’s because we’ve lost our agency. We don’t think we can do anything, and while our brain is essentially in survival mode we’re unable to see what we could actually do. I really do believe that the smallest action is also the hardest. In some cases, it could be a case of simply standing up. What you’ve just done is take back a tiny bit of control and do something you didn’t necessarily want to do. From there, do whatever. Look out the window. Flop on the sofa and watch a movie. Read something. What it does is break the brain’s cycle of negative self –talk by simply distracting it. After that, if there is a particular issue, try thinking about it in a logical way. Finding a solution while in emergency mode is really difficult. But above everything else, do something you want to do, for you.

Is it really that simple? Of course not. Long term depression should be handled by a professional. Likewise with deep underlying trauma. Getting off the sofa won’t solve your money worries. Staring out the window won’t find you a job or bring about world peace. However, it is a first step towards saying, and believing, that “I’m OK”. And a first step is the beginning of everything that has ever been accomplished in this world.

So to sum up, and for the skim readers, yes, it’s OK to not be OK, as long as we acknowledge it, we don’t drag anyone else down with us, we practice some self-care, kindness towards ourselves, and maybe forgive ourselves for feeling like this, we realise that this is temporary, and in the end we take a first step towards being OK again.